How do you art direct the infinite? This was the problem I faced when we started working on Core.

My start in the industry was as a pixel artist in the pre-iPhone era of mobile gaming. It was an exciting time that largely mimicked the golden age of gaming in the 80s. As the technology grew so did the scale and difficulty of making games. They required ever-expanding teams to produce, and the content creation pipelines became exponentially more complicated.

At Manticore, we had the opportunity to change that and make game development more accessible than ever; where small teams or even solo creators could make a commercially viable game in a way that didn’t compromise the advancements in technology, art, and gameplay that has become expected from a modern audience.

I am the Art Director and Chief Visual Officer of Manticore Games. We’ve been hard at work developing Core, a one-stop-shop for game development that provides everything you need to create and publish multiplayer games. It blurs the lines between individual game experiences, allowing you to jump between worlds in a matter of seconds, resulting in an interconnected metaverse of experiences for players to immerse themselves in.

With the recent launch of our Open Alpha and the upcoming Through the Looking Glass art contest, I wanted to share with you what has been guiding our artistic vision for Core. Which brings me back to the original conundrum - how do you art direct the infinite?

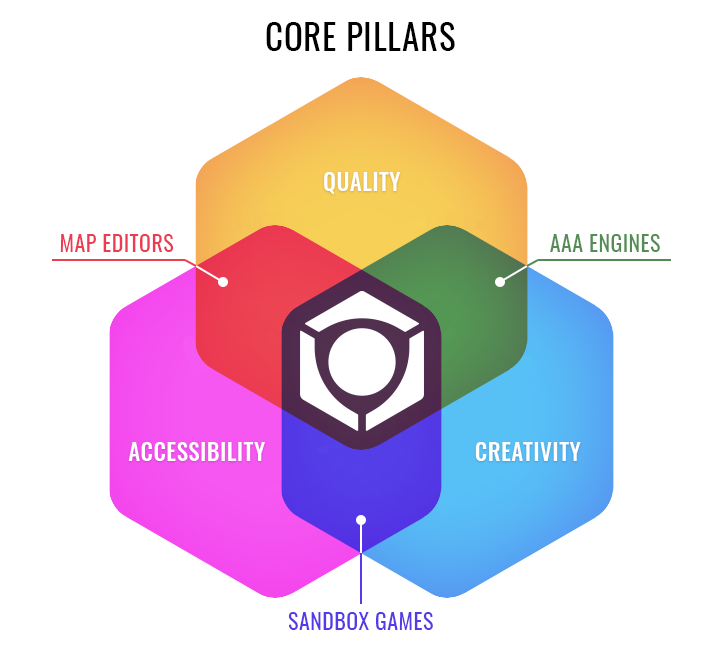

This was unlike anything I had ever worked on before. We weren’t just making a game, but a platform for making any game. We knew Core needed to be the intersection of quality, accessibility, and creativity. If we followed the traditional path of game development, which relies on external tools for content creation, the quality would be subject to the varied skill sets of the community, driving both the overall quality and accessibility down.

To give a sense of the complexity in traditional 3D pipelines, ours involves a myriad of tools including 3DS Max and Maya for low poly modeling, Zbrush and 3D Coat for high poly sculpting, Photoshop and illustrator for 2D concept and graphics, Substance Painter and Designer for texturing, Houdini for VFX, and FL Studio and Pro Tools for audio - and this is by no means an exhaustive list! While the use of these tools provides us with complete artistic control, requiring this of our creators gets us nowhere. There are many existing engines that take advantage of these convoluted pipelines, and mastering them takes years of experience; we wanted to improve on that paradigm.

Inversely, if we were to simply provide high-quality assets, where we would gain in quality and accessibility, we would lose in creativity. We would put ourselves in a position of being the gatekeepers of creativity, where only we can unlock what’s possible to create on the platform. How do we solve this seeming paradox?

Throughout development, we have hosted internal game jams where the entire company would participate and make a game, art, or experience on the platform. During one of our earliest jams, we ran head-first into this problem. We had a budding catalog of high-quality props for people to use in their games, but by the end of the jam, we were completely taken aback by the sheer range of creativity in the submissions.

One game was a 1960’s horror-themed shoot-em-up. Another was a collection of Olympics-themed mini-games. In perhaps the most surprising entry, you played as an egg racing to be first to the frying pan in a giant kitchen-themed obstacle course.

While we were blown away by the creative potential the platform already provided, the problem was we didn’t have any of those art assets. We didn’t have kitchen props. We didn’t have 1960’s themed furniture or sports equipment or guns. Because we didn’t provide assets that each specific game needed, the teams had to resort to using primitives and repurposing objects in unintended ways to achieve their goals. In a twist of irony, despite spending tremendous care and effort into the creation of specific high-quality art content, we actually drove the perceived quality of the platform down.

That was a defining moment for us: we realized that no matter how many assets we made, in an infinite possibility space we would always fall short. We needed a fundamentally different approach. The solution, while instinctively counterintuitive, was to produce assets that embraced the crazy stuff they did. Every asset we made would become a system unto itself for creativity.

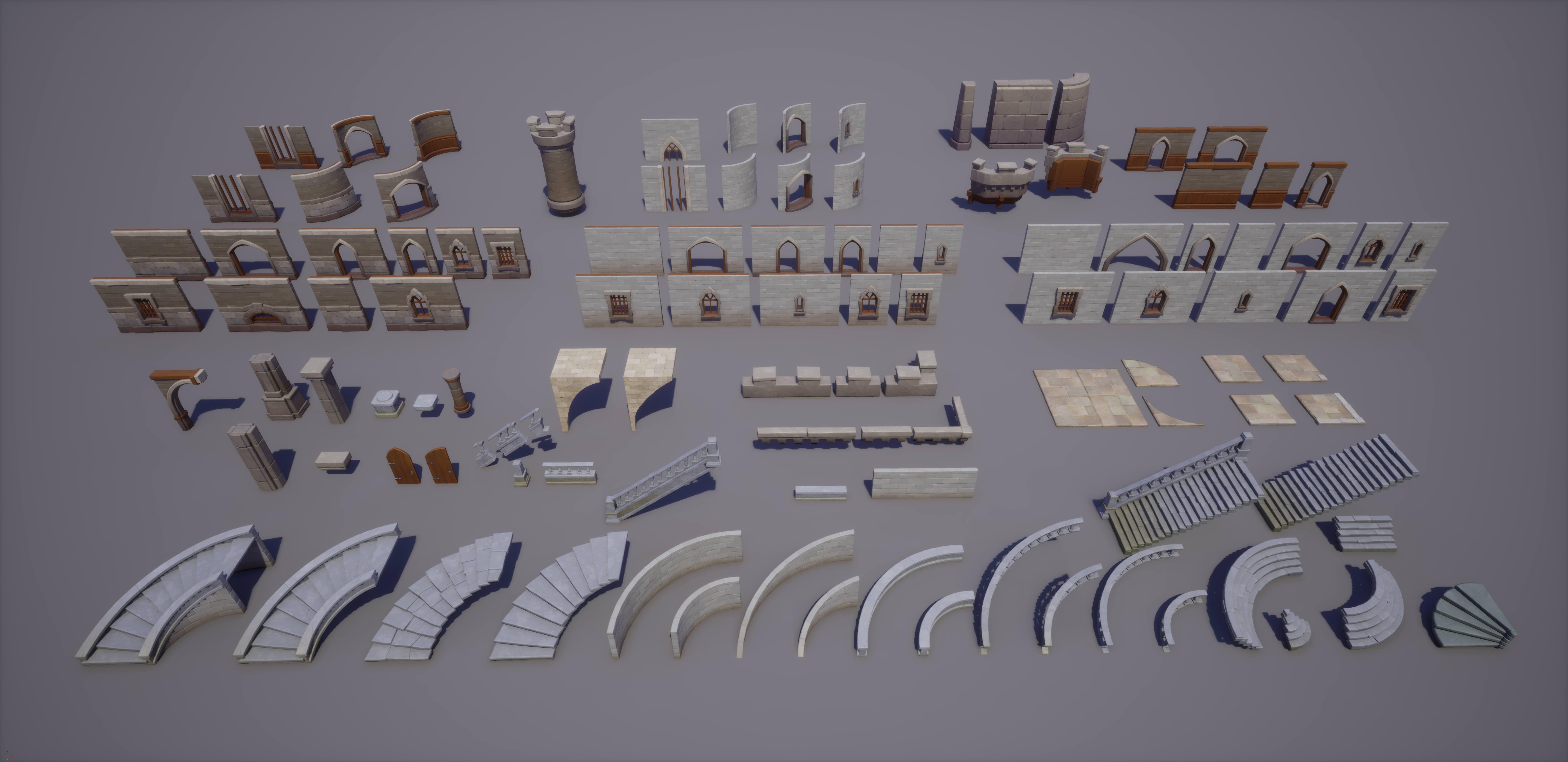

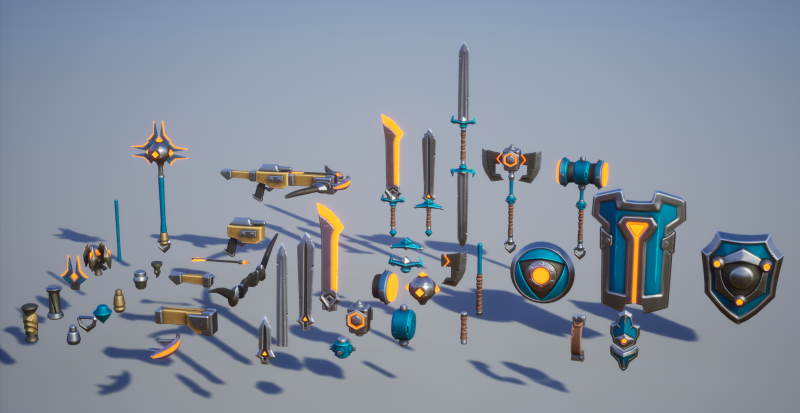

Instead of bespoke props, we’d rely on a “kitbash” mentality when producing assets. A single weapon set could become an infinite range of possible weapons, or an entire environment for that matter, while retaining a high quality bar. No longer did we consider them simply as asset packs, but rather building blocks in a new paradigm for creating 3D art. And we would bridge it all with one cohesive style so any two assets feel natural together; a style playful enough to embrace the metaverse of games and experiences, yet sophisticated enough to not look like a mess or immature.

A tremendous amount of proprietary technology was invented to fulfill these objectives in a way that “just works.” We allow you to apply materials onto any object in a way that automatically retains that object’s baked texture data so you never have to worry about what a “normal” or “ambient occlusion” map is, and it carries over metadata such as what sound effects to play when you walk on them; We have smart materials that tile across objects using triplanar projections allowing you to seamlessly merge objects regardless of UVs; And under the hood, are a myriad of internal optimizations to keep it running fast and smooth. We also expose custom parameters for each and every material and VFX for vastly different looks. Even our audio embraces this parametric paradigm. All of which enables you to fundamentally transform the assets we provide to be uniquely your own.

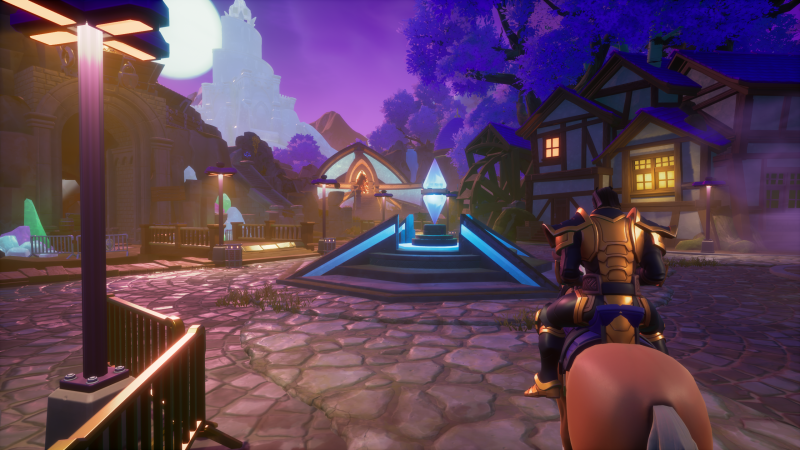

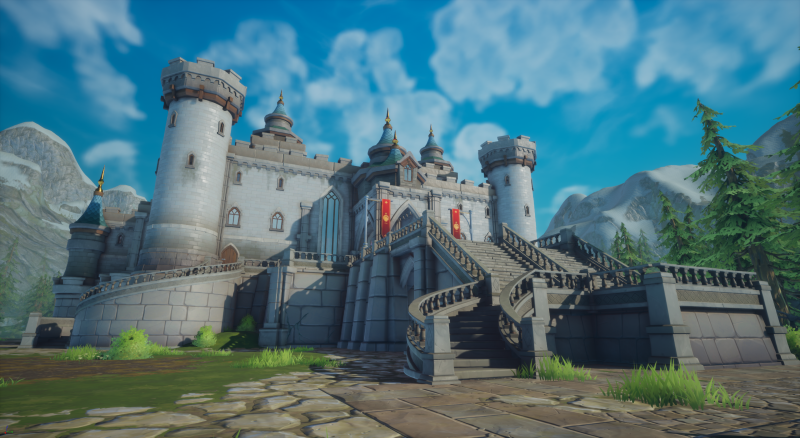

As an example of creativity Core enables, we’ve built Core Plaza, a hub world that explores different themes and showcases many great examples of kitbashing, materials, and VFX. No new assets were created for this world and it was entirely built with the same tools and pieces that every Core creator has access to.

All of these decisions, beyond aesthetic, allow us to deliver on the promise for a true Multiverse. When all of the content already lives on the user’s disk, the games are essentially scripts and definitions for how that content is put together, resulting in extremely fast load times which enables you to hop from game to game as easy as browsing videos on youtube.

Initially, for artists who have dabbled in traditional 3D pipelines, this can sound limiting, but after spending a few hours in Core you quickly realize the power and freedom of this approach. What once took days to create now only takes minutes to achieve commercial-quality results. From personal experience, we often feel less limited when producing art this way because we’re not bogged down with all the intricacies of the modern art pipeline. The translation from idea-to-screen is much more direct, allowing you to produce more, and try more things you otherwise never would have, while maintaining a steady stream of creativity without ever leaving Core.

And we will be continuing to add more parts to the catalog for users to leverage in their creations. Our next patch alone will contain over 100 new castle tileset pieces, 37 fantasy weapon kitbash parts, and a whole slew of new audio and VFX.

In many ways, it reminds me of what I loved about pixel art. While seemingly limited, the constraints of the medium breed creativity and the simplicity of needing only a single application was liberating. It makes anything you could imagine feel achievable, which is perhaps why it has been the medium of choice for so many aspiring developers. I believe we bring the same value proposition to the next generation of creators.

To be clear, it does take a different way of thinking. Mentally, it’s half directed and half opportunistic. It’s about having an idea, yet being flexible with how the pieces express themselves; trying things out, and seeing how they fit. In some ways, it’s a bit like playing with Legos, if the Legos had superpowers. The more you embrace that mentality, the easier you can create amazing things in Core.

I am so consistently surprised by the things our community has been able to achieve, that I’ve had to learn to say that nothing is impossible. Below are some outstanding examples of UGC from the Open Alpha so far, and we’re seeing more amazing things every day.

With that, I’d like to personally invite you to participate in our upcoming Into the Looking Glass art contest. We’ve partnered with American McGee to host the theme set in the world of Alice in Wonderland with great prizes including portfolio reviews by myself and our lead artists. The contest starts May 1st and submissions are due May 31st. There’s no better time to try Core and I’m beyond excited to see what a new generation of artists and designers can come up with. Head over to our contest page for more details.

We’ve put together a number of great resources to help you get started creating great art in Core:

- Core Academy

- Art in Core Overview

- Modeling Complex Objects in Core

- Custom Materials in Core

- Environmental Art in Core

- Visual Effects in Core

- Audio in Core

- Core Games on Youtube

- Core Live on Twitch

- Core Discord Channel

Or if you'd like to jump in right away, head over to CoreGames.com and start creating today!

Can’t wait to see what you come up with!

Dan Fessler